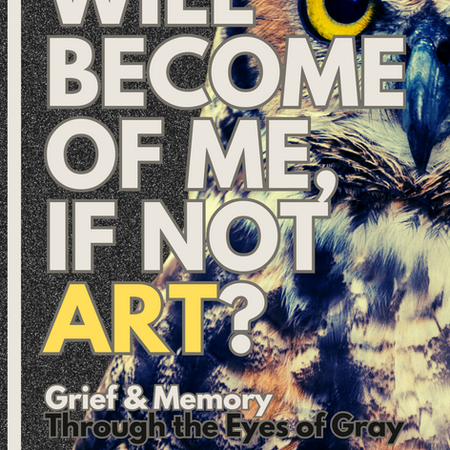

what would become of me, if not art?

Featuring the work of Gray Moore, this show asks the question that all artists encounter in the face of grief: what will become of us, if not art?

This exhibition is the result of a tremendous period of grief Gray experienced in their life, and the symbols that marked it. Over the last few years, Gray has lost 15 members of their family, and is on the path to losing their father to liver cancer. At their home in Colorado, an owl continues to land on the family’s shed, marking each loss and warning of the next. In this series of work, Gray contends with the owl as a messenger while working through their prolonged grief, memory and impending loss.

The title of this exhibit comes from a poem by the artist, discussing art as a means of their survival. [Handouts were provided to guests with said poem on one side and a print of an owl; later in the opening party we hosted a reading of this poem].

"Sometimes I think my heart will fail me

That one day my blood pumping muscle will collapse

From all the 19 years I've been conscious

And all the lives I've lived in between

From all of the fires I've put out and the smoke I've inhaled so others don't have to

One day I will simply fall to the floor.

This life has wounded me, and the people have wounded me, too.

I will die young, from exhaustion.

I think of all the holiday and graduation cards my mom signed for my dad.

The dinners my grandmother burnt for her husband's tongue.

What would become of me, if not art? An apology?

A pause in conversation.

And I would say: this is all I have. This is what I can offer.

And I'm sorry, I'm so very sorry.

Maybe it's not too terrible of a gift...

But it came from me.

I will never know how to give without giving too much."

Owls have been on the Earth for millions of years and have intrigued humans as long as we’ve been around. They appear as messengers of death and bad omens across so much of the world’s myths and folklore, from Native America to Japan and to ancient Greece and Rome.

Lilith, the Sumerian goddess of death, has talons for feet, wears a headdress of horns, and is flanked by owls. Owl statuette artifacts used in funerary contexts. In Mexico, the Mayans believed that an owl hooting long and loud was a bad omen. The screech owl in particular represented Mo An and was an attendant to the Mayan death god Yum Cimil (Johnson & Marcot, 2003). Mo An is the bird of death believed to be a screech owl. Members of the animistic Garo Hills Tribe of Meghalaya, northeast India, call owls dopo or petcha. Along with nightjars, they also refer to owls as doang, which means "birds that are believed to call out at night when a person is going to die"; its cry denotes the death of a person (Nengminza 1996).

Multiple indigenous cultures in the American Southwest see owls as harbingers of bad luck, ill health or death -- or that they serve as vessels for the souls of the newly dead. In ancient Rome, an owl’s hoot was taken to be an omen of impending death, and owl perched on a family home was taken to be an omen of impending death of a family member. In both Greek tragedies like Sophocles' 'Electra' and Roman superstitions, owls were seen as ominous symbols foretelling tragedy and disaster.

Throughout the world, some 82 owl species are closely associated with old forests (Marcot 1995), most awaiting recognition as useful indicators of old-forest conditions. These owls have been called management indicator species by agencies such as USDA Forest Service, who has identified the Northern Spotted owl as such an indicator of old-growth conifer forests of northwestern United States.

And to bring us back to Gray’s artistic landscape, the oldest owl on the fossil record lived in what is now Colorado about 61 million years ago. Now let’s take a closer look at the owl that haunts the artist’s family……

PIECE #1: COPPER ETCHING PRINT

The print as an artmaking method utilizes replication -- this introduces to the viewer the question of recurrence: why does this keep happening to the artist? Why does this cycle of grief keep repeating in their life? [Gray created 15 prints of this owl, one for each family member they have lost over the years.]

The artist can’t process one death before another happens, and another, and another -- the production of a print ties into how the artist approaches this feeling of relentless grief -- memorialize another and another and another as quickly as the process allows.

In our current society and culture we aren’t given time to process grief or life properly. Gray describes their job as an artist as an act of being still, to sit with their experiences of being a human being and translate it to the medium. That act is one of resistance to the capitalist society and its unrelenting pace. But even one death is a massive burden to bear and a difficult one to manage

PIECE #2: SELF-PORTRAIT WITH THE OWL ON THEIR SHOULDER, WEARING THEIR FATHER’S CARHARTT WORK SHIRT

Gray’s father is also an artist, primarily working with whittling and wood burning -- and has also depicted this same owl in past work. The artist wears his work shirt in this portrait to connect the two of them and their practice

Gray sits very still in this portrait, but full of fear of the owl and the possibilities of its power, and its relation to their mortality. The mouse peeking out of their pocket symbolizes their own vulnerable heart, while the owl represents the looming specter of death.

PIECE #3: MEDIEVAL MANUSCRIPT/BESTIARY

The medieval bestiary were essentially illustrated books that described various animals, both real and mythical, along with moral lessons or symbolic interpretations associated with each creature. One bestiary describes owls: “Owls cry out when they sense someone is about to die” – 3244

The primary focus of the bestiary was not scientific accuracy but rather moral edification. Animals were often used as allegorical symbols to convey religious and moral lessons to the readers. This piece features a poem by the artist and further symbolism -- the owl, livers and lilies (a flower that symbolizes sympathy, funeral rites and the innocence restored to dead souls).

Notice the liver on this piece, depicted with a relative amount of scientific accuracy. Related to the opening line of the poem on your handouts, which treats the artist’s heart as a nearly-abstracted scientific organ.

“Sometimes I think my heart will fail me. That one day, my blood pumping muscle will collapse”

Consider this in conversation with the vulnerability conveyed in their self-portrait, where their heart is represented as a tiny animal of prey, cuddled in the fabric of their father’s work shirt.

The poem in this bestiary piece also continues the theme of relentlessness -- “The earth doesn’t stop spinning even when we need it to”. The artist describes themself as unable to sleep: “I dream too much, the owls won’t stop visiting me” -- they fears a moment’s rest will lead to the other dead relatives coming to take their father because they hasn’t been vigilant enough.

PIECE #4: COLLAGE OF CARDS TURNED INTO FOUND POETRY

This piece features cards and messages from loved ones, most of whom are dead now–represented in this show as owl prints hanging along the entrance hallway. This piece features dried wildflowers from the artist’s home state of Colorado. We see Gray processing grief using a natural element separate from the owl here.

The physical process of storing and keeping dried flowers well after they have been plucked from their living fields mimics how a human holds onto cherished memories of those long departed.

From the poem on handouts:

"I think of all the holiday and graduation cards my mom signed for my dad

…What would become of me, if not art?"

Gray has expressed to me how they experience the loss of so many loved ones as a constant energy, akin to anxiety. This question asks, in a way, what would become of the memories, if not art?

It’s best viewed in conversation with….

PIECE #5: VIEW OF THE CREEK, DRAWN FROM MEMORY

This drawing shows the view from the bench Gray’s family bought to memorialize their grandfather who died in Colorado. It shows a creek they’d spend summers in, playing and catching crayfish/crawdads with their grandfather.

Both of these pieces examine grief and bittersweet memory, and feel deeply tied to Gray’s artistic practice of sitting in the stillness of an emotion or memory for long enough to conjure it and create something from it

PIECE #6: PORTRAIT OF GRAY’S FATHER IN THE DINER

This portrait of the artist’s father depicts the recurring breakfasts they and their father would have together after their parent’s divorce -- always at the same time, at the same diner -- and the residual feeling of those memories. Despite all the time spent together, Gray still feels that they never really got to know each other that well, as shown in the composition by the condiments in the foreground, separating the viewer from the subject.

This portrait stands as an answer to the previous question asked by the poem, What will become of the memory, if not art?

Gray finds themself in a unique position of attempting to create a living eulogy for their father through their current artistic explorations. The owl, the poetry, the portraiture, and an acceptance of the parallels between their artistic practices (those being woodburning and woodblock printing, and the subject matter of Colorado's ecological landscape, in Gray's case, specific to the owl).

Across from this we have another memory, this time looking toward the future…..:

PIECE #7: SELF-PORTRAIT AS A BABY, BLOWING OUT BIRTHDAY CANDLES

It’s titled “maybe this year will be better” -- and shows the artist welcoming a new year, and looking to it with hope, despite all evidence to the contrary

There’s also something foregrounded here, this time a flame -- something dynamic and almost alive, bringing light, etc.

From the handout poem:

“From all of the fires I’ve put out and the smoke I’ve inhaled so others don’t have to. One day I will simply fall to the floor.”

This piece serves as a radically hopeful other option. As opposed to falling to the floor and dying themself, this piece has the courage, in the face of immense grief and loss, to hope that as the artist watches the cycle begin once more, that this time will be better. That this time will be the last.

This piece both ends this loop of work and begins a new one. In conversation with the theme of grief, the choice of drawing themselves as a baby visibly starts the cycle of life all over again. [We hosted this opening in April, a welcome match to these themes of rebirth. It doesn't hurt that Gray was actually born in the spring, too].

The significance of print as the medium for this piece is reiterated from what we saw in the owl series. However, there is an added significance to this print in the fact that, instead of a copper etching it is a wood relief. The closest Gray has ever gotten in their artistic practice thus far to replicating the woodworking that their father has pursued for all of his adult life.

Power in Numbers

Programs

Locations

Volunteers

Project Gallery